免疫檢查點療法 抗癌新利器

今年1月31日,史丹福大學醫學院(Stanford University School of Medicine),免疫治療權威羅納•利維(Ronald Levy)教授與其研發團隊在國際重量級期刊《Science Translation Medicine》發表了一種革命性的新型免疫檢查點治療方式。這種新方式只需「局部、單次、低劑量」的投以免疫檢查點藥物,即可治癒多種不同類型的小鼠腫瘤,更成功讓小鼠對腫瘤產生全身性的免疫治療效果。鑑於此療法在動物實驗取得的驚人成效,史丹佛大學目前已著手進行臨床試驗準備,預計前期將招收15位淋巴癌病患進行人體實驗,並視實驗進展再擴及到其他腫瘤治療。

羅納教授所使用的是「OX40抗體」與「CpG DNA」兩種藥物的複合配方(後簡稱-復合藥物)。其中OX40蛋白是T細胞上一個重要的免疫檢查點蛋白,與目前主流的PD-1/PD-L1抑制藥物不同,OX40蛋白對免疫系統像是油門開關,而抗體藥物與OX40的結合將打開此開關,進而活化CD4與CD8-T細胞的功能。

CpG DNA是細菌體內常見的未甲基化特殊DNA序列,主要與TLR9接受器結合並活化多種免疫細胞,CpG DNA過去即被證明在腫瘤治療上具顯著療效,然而由於藥物無法專一性運送至病灶,而系統性注射又容易導致副作用過強等問題,因此CpG DNA過去大多被當成疫苗佐劑使用。

在90隻接受復合藥物治療的淋巴癌小鼠上,有87隻小鼠腫瘤如奇蹟般地消失,更驚人的是,當他們將複合藥物直接注射於單一腫瘤位置後,小鼠身上不同位置的同源腫瘤也會同樣完全消失。這證明此療法具如疫苗般的全身性效果,有很大機會用於轉移性癌症治療。除此之外,羅納教授更進一步在乳腺癌,結腸癌,黑色素癌小鼠模式上進行測試,也都看到類似的治療效果。這暗示此復合藥物可能是能用於各種癌症治療的革命性療法。

2月2日,默沙東大藥廠公布2017年財報,其主力產品KEYTRUDA去年銷售成長172%,狂賣近40億美元,而其對手藥物-必治妥大藥廠的OPDIVO,銷售也成長30%達49.5億美元。免疫檢查點藥物無疑已成為當前腫瘤治療最耀眼的明星,然而明星光環下,藥物應答率的不彰與昂貴的藥價,一直是免疫檢查點療法最大的瓶頸。

以KEYTRUDA為例,平均藥物應答率只有20-30%,然而治療方式卻是每三周一次施打每單位體重(公斤)2毫克的劑量,一直投藥到腫瘤消失為止,其療程可能長達1年,而藥物總花費高達300萬-400萬台幣。反觀本文中的複合藥物,不僅在小鼠試驗中展現了驚人的96.6%的治癒率,且如疫苗般僅需「局部、單次、低劑量」的治療方式,大幅下修藥物需求與治療花費,同時也能有效避免高劑量、長期且持續性給予免疫檢查點單抗藥物所帶來的副作用。

目前所有的免疫檢查點藥物療程與大部分的結合治療研究,都是沿用傳統癌症藥物的邏輯,以高劑量持續的全身性給藥方式。這種治療方式,對於生物體複雜的免疫系統或許不是最好的選擇。去年10月15日,在《Clinical Cancer Research》和《Cancer Immunology Research》上,同日發表的兩篇文章便發現,合併兩種免疫檢查點藥物治療時,兩藥分別投藥的時間將嚴重影響治療效果,一味持續性的給藥反有不利影響。

本篇研究更進一步證明,真正成功的免疫治療應該是打帶跑(hit-and-run),不需要長期且持續性的提供藥物刺激。只要搭配正確的藥物配方與施打方式,後續的長期治療由被活化的免疫細胞接手即可。雖然複合藥物在人體的療效仍待驗證,然已為未來免疫治療開啟了新的契機,藉由「局部、單次、低劑量」藥物治療,一次性的根治腫瘤將不是夢想。

免疫檢查點療法從第一個藥物YERVOY被美國FDA核准上市後,短短幾年已有六個單抗藥物被核准上市,分別針對CTLA4、PD1與PD-L1等標的,用於治療超過10種不同的癌症。近年中國國家食品藥品監管局也動作積極,繼去年底受理了信達生物製藥所生產之PD-1單抗藥物上市申請後,1月18日更快速批准了李氏大藥廠PD-L1單抗藥物之臨床批件。

然而在各方積極追逐效價更高、結合力更強、效果更持久的各種免疫檢查點單抗藥物的同時,或許我們更應該靜心思考,免疫檢查點療法仍屬早期發展階段,許多相關的分子機制科學界仍是一知半解,我們很可能至今仍未弄清楚免疫檢查點藥物這項武器的正確使用方法。

(作者是鑽石生技投資分析室分析師)

Cancer “vaccine” makes tumours vanish

A DNA-antibody combination banishes cancer in mouse models, with human trials about to start. Andrew Masterson reports.

A vaccine effective against a wide range of cancers is one step nearer.

GOMBERT, SIGRID/GETTY IMAGES

A combination of a tiny segment of DNA and a specific antibody injected into a solid tumour has been shown to remove not only the target tumour, but also others in the body, at least in mice.

So confident are they of the effectiveness of their approach, scientists at the Stanford University School of Medicine in the US are this month starting a clinical trial using human patients.

Like several other treatments, the combination therapy, reported in the journal Science Translational Medicine, prompts the body’s own immune system to tackle tumours. However, unlike others, it functions as a one-size-fits-all strategy. To a significant extent, it seems, it is not necessary to first identify the type of cancer involved.

“When we use these two agents together, we see the elimination of tumours all over the body,” says oncologist Ronald Levy, one of the authors of the study.

“This approach bypasses the need to identify tumour-specific immune targets and doesn’t require wholesale activation of the immune system or customisation of a patient’s immune cells.”

The Stanford team’s strategy works by exploiting the curiously ambivalent relationship between cancer tumours and immune cells called T cells. The latter function to attack bodily invaders through detecting abnormal proteins.

Initially the T cells will recognise such proteins on the surface of cancer cells and enter the developing tumour. However, as the tumour continues to grow, T cell activity drops off. In a sense, the immune system gives up.

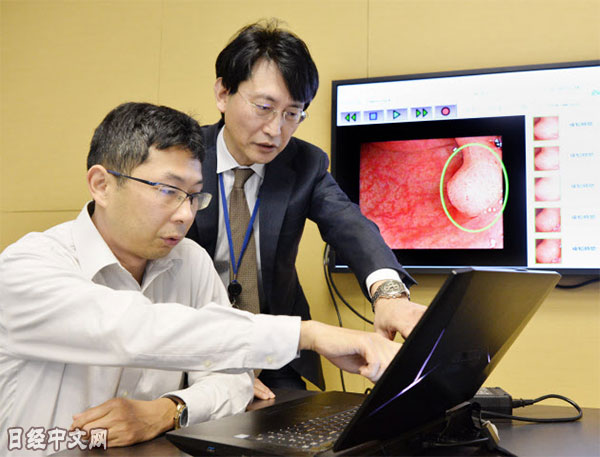

Levy and his colleagues found a way to reactivate the moribund T cells. To do this, they inject a target tumour with a couple of micrograms of a short stretch of DNA called a CpG oligonucleotide. This works with nearby immune cells to activate a receptor called OX40 on the surface of the T cells.

CpG oligonucleotide is already used to bolster several types of cancer treatment.

At this point, the second agent – an antibody that binds to OX40 – comes into action, revivifying T cells, but only those within the tumour. This is important, because the combination effectively generates a cohort of immune cells pre-programmed to attack only cancer-specific proteins.

Once the process is under way, the scientists report, the tumour-hungry T cells leave the initial site and distribute through the body, attacking any and all other similar tumours they find.

“Our approach uses a one-time application of very small amounts of two agents to stimulate the immune cells only within the tumour itself,” explains Levy.

“In the mice, we saw amazing, body-wide effects, including the elimination of tumours all over the animal.”

The therapy has been trialled against several different types of cancers in mice. The first trial involved 90 animals with lymphoma tumours on both sides of their bodies. In each, only one tumour was treated. The paper details that 87 out of the 90 were cured. The cancer returned in three cases, but went into permanent remission after a second treatment.

Mice carrying breast, colon and melanoma tumours were also treated successfully. Trials were also conducted on mice genetically engineered to develop multiple breast cancers. In many cases treating the first tumour to appear prevented others arising.

While the treatment is effective against a range of cancers, each application conditions T cells to fight only one. Tests on mice with two types of tumour found that only the type treated went into remission, leaving the other unaffected.

“This is a very targeted approach,” Levy says. “Only the tumour that shares the protein targets displayed by the treated site is affected. We’re attacking specific targets without having to identify exactly what proteins the T-cells are recognising.”

An initial human trial will get underway soon, with the researchers looking to recruit about 15 patients with low-grade lymphoma.

Injection helps the immune system obliterate tumors, at least in mice

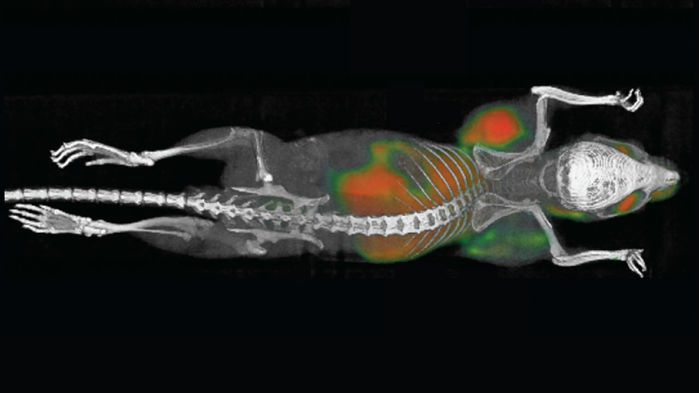

Tumors are growing on each side of this mouse’s body just behind its forelegs.

SAGIV-BARFI ET AL./SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Our immune cells can destroy tumors, but sometimes they need a kick in the pants to do the job. A study in mice describes a new way to incite these attacks by injecting an immune-stimulating mixture directly into tumors. The shots trigger the animals’ immune system to eliminate not only the injected tumors, but also other tumors in their bodies.

“This is a very important study,” says immunologist Keith Knutson of the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida, who wasn’t connected to the research. “It provides a good pretext for going into humans.”

To bring the wrath of the immune system down on tumors, researchers have tried shooting them up with a variety of molecules and viruses. So far, however, almost every candidate they’ve tested hasn’t worked in people.

Hoping to develop a more potent approach, medical oncologist Ron Levy of Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, and colleagues used mice to test the cancer-fighting capabilities of some 20 molecules, including several types of antibodies that activate immune cells. The researchers first induced tumors by inserting cancer cells just below the skin at two different locations on the animals’ abdomens. After tumors started growing at both sites, the scientists injected the molecules, alone or in combination, into one tumor in each mouse. They then tracked the responses of both tumors.

.

.jpg)